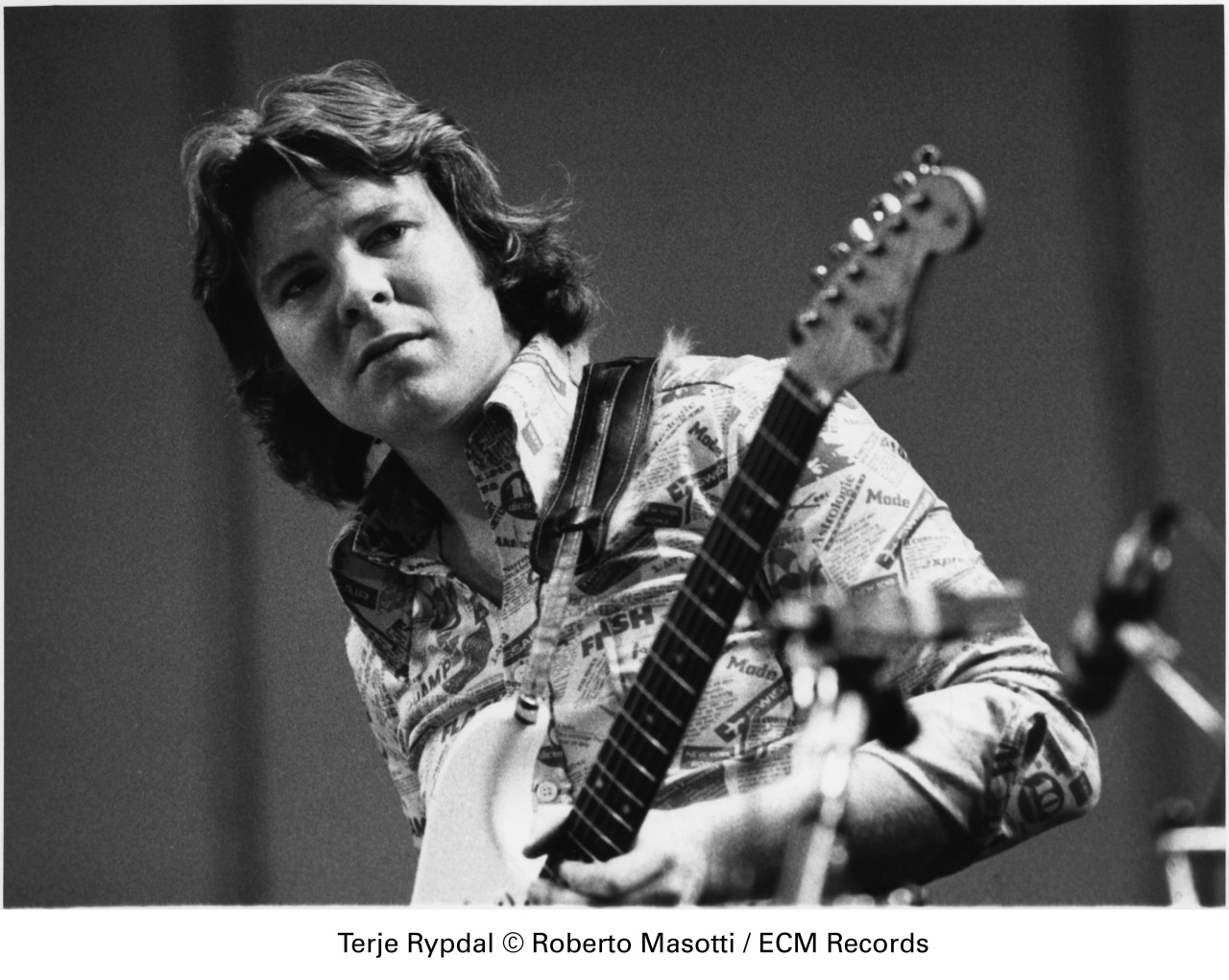

Terje Rypdal’s Odyssey: New York and Beyond the Infinite

An interview with Terje Rypdal from 2012 by Gideon Egger and Ying Zhu.

Terje Rypdal uses a cane to climb the stairs onto the stage at Le Poisson Rouge, for a rare concert in New York City. The crowd cheers and he waves his cane in recognition. He sits down, picks up his red Fender Stratocaster, and proceeds to unleash a barrage of color.

“When I have a really good guitar sound—like in New York–it sort of opens up and there is some brightness shining and colors.”

Rypdal can wow you with speed and chops as well as any virtuoso, but he can do more: he can paint a picture, tell a story, inspire quiet reflection, stir memory, elicit emotion. Rock guitar virtuosity is rather common these days, but these gifts of evocation are as rare as ever.

For ninety minutes Rypdal, trumpeter Palle Mikkelborg, keyboard player Ståle Storløkken and drummer Paolo Vinaccia lead the audience on a journey through genre-defying soundscapes, alternately dense and austere, beautiful and intense, familiar and adventurous.

Mikkelborg’s sparse and haunting lines invoke Miles Davis. The two worked together on Davis’ 1989 album Aura (Mikkelborg produced the record and composed all the tracks) and the whole concept of combining rock and jazz really dates back to Davis’ seminal Bitches Brew album, released in 1970.

Bitches Brew started a new genre and the 1970s saw a vast outpouring of jazz-rock-fusion combos and recordings.

But fusion in the ‘70s and ‘80s tended to degenerate into what detractors call “fusak,” a showcase for flashy technique and fancy chord changes, where the songwriting was at best an after-thought. The songs themselves, qua songs, often sounded like electronic elevator music.

Terje Rypdal took an entirely different approach.

In fact, while Rypdal often cites Davis’ Bitches Brew as an influence–he even wrote a piece in homage to it, Vossabrygg, released in 2006–his music is really as much a continuation of Duke Ellington’s “third-stream,” combining jazz and classical music, as of Miles Davis’ fusion of rock and jazz.

But whereas Ellington’s classical influences were primarily romantic, Rypdal is principally inspired by two modern composers: György Ligeti and Krysztof Penderecki.

Rypdal first heard Ligeti’s music in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey.

People often assume that Ligeti’s Requiem was written for that film. This assumption is wrong but certainly neither foolish nor unreasonable. It is a testament to Kubrick’s genius that the images and the sounds mesh so perfectly.

A concert-goer, someone who expects “classical music” to sound like Mozart or Vivaldi might hear Ligeti’s Requiem and experience its intense dissonances and tensions as ugliness. But a movie-goer–watching 2001–experiences Ligeti’s Requiem as the perfect complement to the confusion of lights and colors streaming across the screen.

For Rypdal it was a transformative experience.

“I heard Ligeti’s music and I decided then to try to make a living as a composer and guitar player.”

But Rypdal’s interest in Ligeti also led him to Penderecki.

“I went to a record store the day after I saw that movie and asked about Ligeti’s music and they didn’t have anything but they said `we have Penderecki.’ And so I bought some of Penderecki’s albums.”

Eventually Penderecki and Rypdal met and worked together.

“He conducted a piece called Actions[for Free Jazz Orchestra] and I was in the band so I had all these scores. So I asked for a meeting with him and since then I’ve met him a couple of times. He’s probably absolutely the most important to me. I’m really a fan of his music.”

In fact, by the time A Space Odyssey came out, in 1968, Rypdal had already had some success in his native Norway as a rock guitarist, first with the band Vanguards, and then with the band Dream.

Rypdal started taking piano lessons when he was five. He also played the trumpet. At age twelve he taught himself how to play the guitar. He joined the Vanguards while still a teenager.

With Dream, Rypdal began covering Jimi Hendrix tunes.

“Dream actually played a lot of his first album Are You Experienced? We did that live. On the Get Dreamy album there’s a tribute to Jimi Hendrix [Hey Jimi].

“I had a girlfriend at the time and she was going to Sweden to visit a friend of hers who was one of Jimi Hendrix’s Swedish girlfriends.

“So I gave her the album to give to Jimi Hendrix and I wrote on the back of the album that we had written `Hey Jimi’ as a tribute.

“I didn’t know if he got it or what happened to it, but just about five years ago I found out that Hendrix kept it–it was one of the albums in Hendrix’s collection that was sold to a record collector in Los Angeles–and it turned out that Hendrix played it quite a bit. It makes me very proud; when he was alive I never heard anything.”

But even after experiencing success at a young age, Rypdal knew that making a living as a musician and composer would be tough.

“My father was a musician–a military musician–and I knew from him that it would be very difficult. In the beginning I planned it just as a hobby. When ECM came along I got a chance to make a living. But it wasn’t really planned. But I’ve been very lucky. If I didn’t have that ECM connection, if I only gave concerts in Norway I would probably have to do something else also.”

After Dream, Rypdal released one more rock album, Bleak House, in 1968, under his own name, on the Polydor label.

After Bleak House, Rypdal began playing more jazz-influenced instrumental music with George Russell and Jan Garbarek, both of whom were signed to the German label ECM. One song that Rypdal wrote for a Garbarek session didn’t make it onto the final release, but Manfred Eicher, the founder of ECM, suggested that Rypdal record his own album for the label.

Eicher encouraged Rypdal to develop his own sound. That sound began to emerge on his eponymous debut for ECM in 1971, continued to develop on the following albums, What Comes After, and Whenever I Seem to be Far Away, both released in 1974, but really came to fruition with the album Odyssey, in 1975. Originally released as a double LP, when the CD version of Odyssey was released in the ‘80s, one twenty-three minute song, Rolling Stone, was sacrificed. That omission is finally being redressed, as ECM is now re-releasing Odyssey as a three CD box set, including Rolling Stone, and an entire CD’s worth of unreleased material including an early version of the song Waves.

In the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, Rypdal began to incorporate a harder, more metal-influenced sound, in the recording To Be Continued, for instance, with drummer Jack DeJohnette and bassist Miroslav Vitous, and then with his band The Chasers.

In the ‘90s he began to release recordings of some of his classical compositions, including: Undisonus Op. 23 for Violin and Orchestra a piece that won the Norwegian Composers Association’s prize for “Work of the Year” in 1984.

Classical influences were apparent on his early ECM records, in songs like Rainbow, and Whenever I seem to be far Away, but those pieces were in part improvised.

But Rypdal had been writing orchestral since about the time he joined ECM.

“The first real composition goes back to 1970, and I guess I started to write it in ‘69. The first one was called Eternal Circulation.”

Rypdal’s compositions are contemporary, but just as classical music has influenced his writing for guitar, his rock and jazz background has influenced his classical music.

“I took some classes in the beginning with a very good Norwegian composer named Finn Mortensen. In his classes he talked about a lot of things, for instance Schoenberg, so I know how to write in that style but I never used it. I was so used to using melody and chords, that from the beginning I broke a lot of rules in contemporary music with writing melodic things.”

Other than the Odyssey re-issue (Odyssey: in Studio and in Concert) Rypdal’s most recent ECM release is the 2010 album Crime Scene, featuring the same quartet that performed at Le Poisson Rouge, along with the Bergen Big Band, in a live recording of a suite Rypdal was commissioned to write.

“I was commissioned to write for the Bergen Big Band and I had the title for it and just before I wrote it I had a really big operation, so I was actually sitting in a wheel-chair while I wrote that piece.

“The structure was quite open, based on a lot of different songs. I asked Paolo [Vinaccia] to make his drum part and he tried to make something using samples from gangster movies and then he suggested using these throughout the piece. So it turned out more organized than it was in the beginning.”

(Photo by Arnie Goodman)

Rypdal had a strange experience during the rehearsal for Crime Scene.

“A song called It’s not been written yet. It’s very loose, just repeating things from different places and layers, but it sounded very close to a dream I had where I came to rehearsal and everything was wrong, and it ended up I woke saying that I understand why I had had so many troubles, because we were rehearsing something that I hadn’t written yet. So when we came to that song during rehearsal I told Paolo, `This is so close to what I actually heard in that dream.’ So that became the title.”

(Photo by Arnie Goodman)

With all of his various influences, and independent of any particular genre, there is still a distinctive “Rypdal sound.” With so many disparate ingredients, a lesser talent might easily make a sonic mess, but Rypdal’s music always has an organic quality, as if it were created by nature.

(Photo of Norway from Shutterstock)

In 1995 Rypdal released an album called If Mountains Could Sing, and this may be the best possible description of his music.

Indeed, Rypdal finds nature not only inspirational but essential to his creative process.

“I’ve been living here [Tresfjord, Norway] for almost twenty-five years now, but before that I moved back to Oslo for a few years but I could never compose there. That’s why I moved here. It was just a cabin then but I’m very dependent on nature, on the mountains around here. It doesn’t work in the city for me.”

(Photo of Tresfjord, Norway, by Lars Kristian Flem)

Pingback: Blues Rock, Jazz Rock, Psychedelic Rock, Norway 1960s (Tracks) Terje Rypdal – “Dead Man’s Tales” – Sound Space